Deep seabed mining

Status: 02/22/2023 06:25 AM

The International Seabed Authority has until summer to make a decision on commercial deep sea mining. It is still relatively unknown what mining means for the ecosystems there.

Written by Jasmine Appelhans, NDR

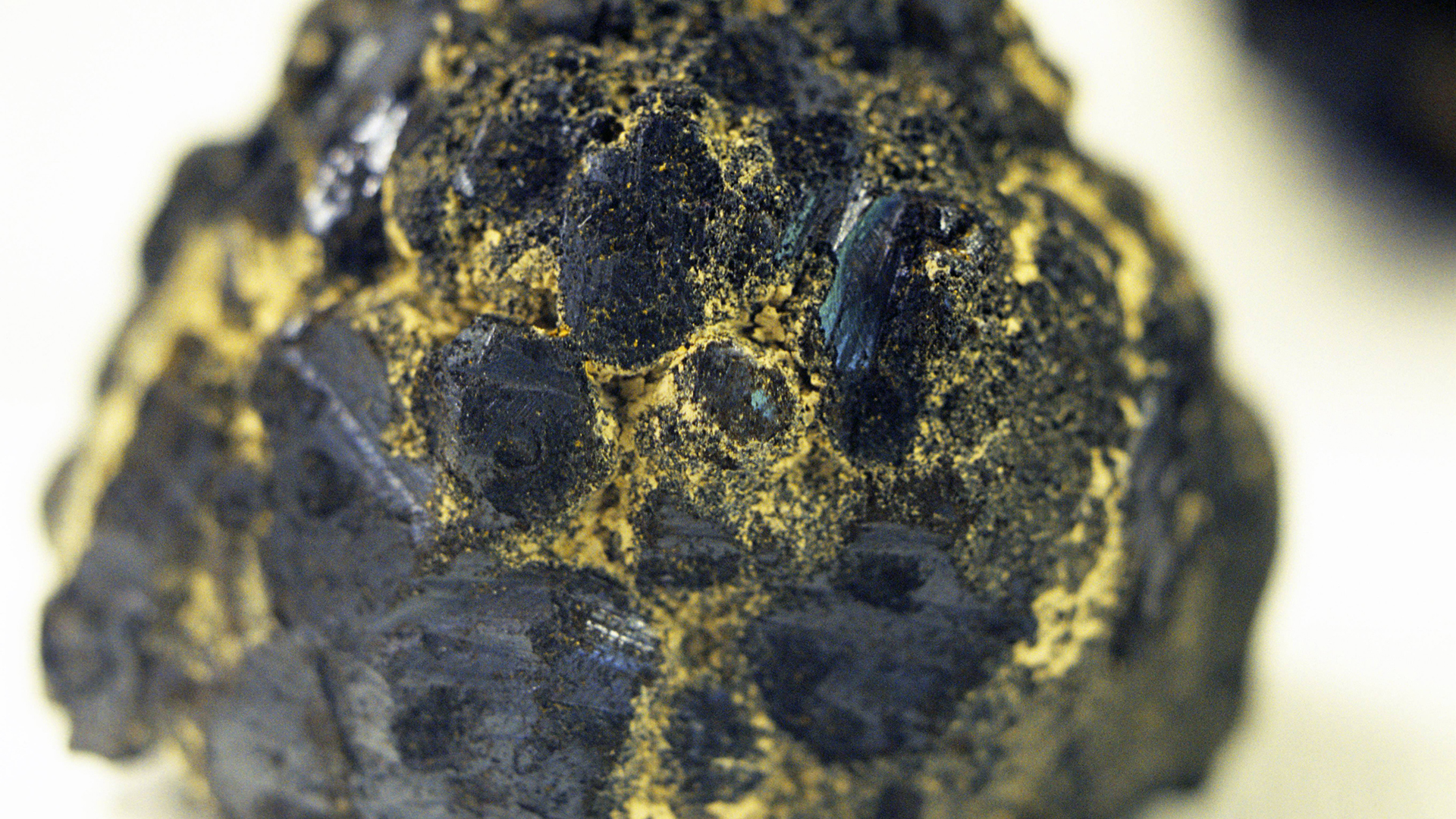

In some offshore areas, the coveted objects lie close together on the seafloor: manganese nodules that contain lots of copper, nickel, and cobalt in addition to the manganese and iron that give it its name. These are minerals that are not very common on Earth but are of great economic benefit. For example, they are used for batteries in electric cars and in solar and wind power plants. They play an important role in the transmission of energy.

Therefore, some companies and governments are already testing prototypes that can collect manganese nodules in the future. For example, the Belgian company Global Sea Mineral Resources has developed such a device. Weighing approximately 20 tons, it operates on chains and uses a water jet to create negative pressure that sucks manganese nodules into the device.

“This is bigger than the Leopard 2 tank,” says Matthias Haeckel. He is a biogeochemist at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Kiel and leads a European project on the consequences of deep seabed mining. “The upper centimeters are completely removed from the sea floor with the device – and later released into the sea elsewhere.”

Marine biologist Sabine Gollner of the Royal Netherlands Institute for Marine Research in Texel explains that this method, which is also used by other companies, leaves visible traces on the sea floor: “After dismounting, you can see a field that has been plowed,” she says. Traces of the first attempts can still be seen in the 1970s and 1980s. From a purely visual point of view, almost nothing has changed in the structure of the floor since then.

All animals and microorganisms that live in the sand at the bottom of the deep sea disappear into the devices along with the sea floor. Besides the manganese nodules, any corals, sponges and anemones that rest on the hard surface of the nodules are also sucked up. This includes species found only on manganese nodules in the deep sea, such as the sponges on which the ghost octopus lays its eggs.

According to Matthias Hegel, the method used to collect the nodules could thus cause long-term damage to the ecosystem. Because in the deep sea, many animals grow very slowly. For one thing, because so little food goes deep that plants cannot grow in the dark. On the other hand, because the metabolism of many animals is very slow in the cold.

“With models, you can try to calculate how long an ecosystem will need to recover — and then it’s more like centuries to millennia than years or decades,” says the biogeochemist.

Sabine Gollner would like to know exactly how long it would take for large animals to settle again after they moved such a device across the seafloor and collected manganese nodules, and whether anemones, sponges and corals could also grow on hard surfaces beyond exploring manganese nodules now.

To do this, she experiments with artificial manganese nodules made of ceramic. It is still not known how long it takes for the animals to grow to full size. “Are anemones, corals, sponges, for example, five years old, 50 or 500 years old? We don’t know that at the moment,” she says.

Since 2019, tires with real, clean, synthetic tubercles have been present at a depth of 4,500 meters in the Pacific Ocean. Sabine Gollner and her team are currently investigating what exactly grows on the tubers in the lab. However, after two years of growth, hardly any animal could be seen with the naked eye.

The experiment would last for thirty years. Only the next few years will tell if there is enough time for animals like sponges and corals to settle on the nodules again.

Not much is known about the deep-sea ecology. In order to be able to make political decisions about economic projects that overlap with nature, so-called ecosystem models are usually necessary. The entire ecosystem is considered and the consequences of interventions are simulated.

“This is something that does not yet exist in the deep sea because we do not yet understand the general context of the ecosystem,” says Matthias Hegel of GEOMAR. Until now, researchers have not even been able to identify the most important species in this order. “It is likely that the diversity of species on the deep sea floor will be a critical factor,” Heigl says.

Meanwhile, seabed allocation negotiations at the International Seabed Authority in Jamaica are already in full swing. It is responsible for deciding whether, and how, nodules and other mineral-rich rocks such as the extinct black smokers and iron-manganese crusts in submerged mountains are in international waters. So far, the authority has only issued licenses to research potential mining, but they may not be implemented yet.

Time is of the essence as the island nation of Nauru wants to start mining. He submitted an application to the authority in the summer of 2021, which led to the so-called two-year period, explained legal researcher Alexander Bruelz from the University of Hamburg. “This means that by the summer of this year the regulations on exploitation should be in force.” If there is no agreement by then, the law that was negotiated will apply – with unknown consequences for the animals of the deep sea.

Negotiations will continue at the International Seabed Authority on March 7. Because the consequences of deep-sea mining remain largely unknown, last November the German government decided not to support deep-sea mining projects in international waters. Until more is known about Deep Sea, it is suspending its participation.

“Tv expert. Hardcore creator. Extreme music fan. Lifelong twitter geek. Certified travel enthusiast. Baconaholic. Pop culture nerd. Reader. Freelance student.”

More Stories

Shepherd's cheese and feta: Are all cheeses sheep's cheese?

“The kind of stone we were hoping to find.”

The closest supernova to Earth in years produced a surprisingly small amount of gamma radiation